Heart rhythm consultants, primary care physicians, specialist registrars, nurses and physiologists may be requested to review ECGs or advise on cases where antipsychotic-induced QT prolongation is suspected or evident. The British Heart Rhythm Society has issued the Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Patients Developing QT Prolongation on Antipsychotic Medication to support them. The guidance is adapted from the most recent Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry, issued in 2018.1

When considering the risk of death with schizophrenia, it is important to recognise that this condition carries a mortality from its psychiatric effects. Nearly one-third of the excess mortality in schizophrenia is attributable to a significantly higher risk of suicide – 5% risk over the patient’s lifetime – with an additional 12% due to accidental death. Antipsychotics reduce adverse outcomes on mortality in the schizophrenia population.2–5

The overall and cardiovascular mortality distributions follow a U-shaped curve in relation to antipsychotic dose with patients taking no medication and those taking the highest doses having the greatest mortality.

This indicates that antipsychotics can protect patients against the consequences of schizophrenia, including suicide, at low and medium cumulative doses; compliance is critical and high doses should be avoided.6 Indeed, mortality is 40% lower in patients with schizophrenia who use antipsychotics than those who do not.

Long-acting injection (LAI) use is associated with an approximately 30% lower risk of death than oral use of the same medication, most probably because this ensures adherence and sustained drug action. Second-generation LAI antipsychotics and oral aripiprazole have the lowest mortality.7

The mortality data also indicate that people with schizophrenia have higher fatality rates due to natural causes than the general population in the US. Cardiovascular, respiratory and metabolic disorders are 2–3 times more prevalent in people with schizophrenia.3,4 Some antipsychotics cause increased appetite and weight gain, and can also directly cause metabolic syndrome, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and insulin resistance, which probably leads to greater cardiac mortality rates. Unhealthy lifestyles, polypharmacy and suboptimal healthcare are all regarded as contributing factors to the risk of higher mortality.

Case-control studies have suggested that the use of most antipsychotics is associated with rate of sudden cardiac death that is two- to three-times higher than in the general population –15 per 10,000 years of drug exposure.8–12 This is substantially lower than the mortality associated with uncontrolled psychosis.

Most antipsychotics (which are prescribed for schizophrenia and other psychoses, agitation, severe anxiety, mania and violent or dangerously impulsive behaviour) prolong the QT interval primarily through K channel blocking effects. QT prolongation increases the risk of torsades de pointes and sudden cardiac death, although the evidence base to suggest this is exponential is limited; there are exceptions in that some drugs prolong the QT interval but do not increase dispersion of repolarisation. However, more robust data indicate that, once the QTc interval is >500 ms, the risk of torsades de pointes in significantly increased.11

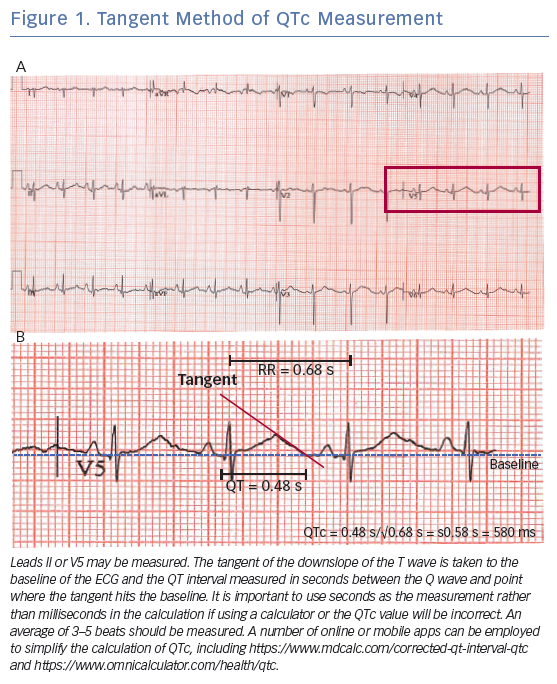

Accurate QT measurement may be challenging because the presence of U waves makes it difficult to determine the end of the T wave, but the QT interval can be easily measured using the ‘tangent method’ if automated measurement is not available or appears incorrect. Correct QT measurement is key to minimise the risks of over- or under-estimating the QT interval and wrongly stratifying patient risk.

To minimise inconsistencies, it is best to measure the tangent of the descending T wave to baseline in leads II or V5.13,14 This technique has been found to be the most reproducible among experts and non-experts alike (Figure 1).

Many patients will have a resting tachycardia (>100/min) on medication so a correction for heart rate using the Fredericia formula (which uses the cube root of the RR interval) is recommended rather than Bazett’s as the latter will overestimate the QTc at higher heart rates. A simple online calculator to work out the QTc can be found at https://www.mdcalc.com/corrected-qt-interval-qtc. Regardless of which of these forumulae is used, detection of QTc >500 ms should prompt review.

Quantifying Risk

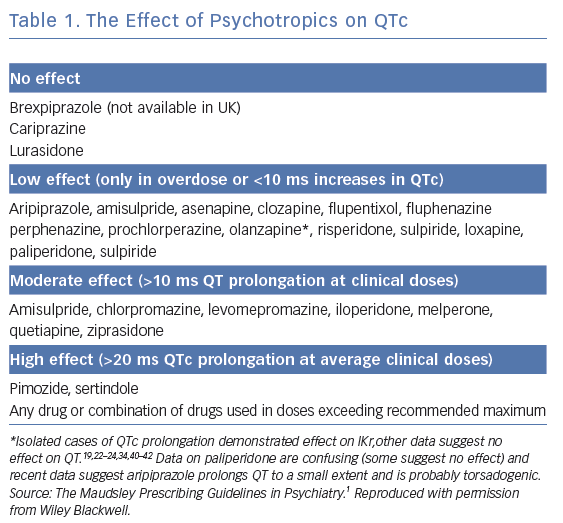

Drugs are categorised here according to data available on their effects on QTc (Table 1).

In summary, currently the only antipsychotics not associated with QT prolongation are:

- lurasidone;

- cariprazine; and

- brexpiprazole.

As a general rule, if the QTc is significantly prolonged (>500 ms) with no other reversible causes (see below) or any another antipsychotic, the patient should be switched to one of the three drugs above, but clinicians should be aware that the risk of relapse is increased to a small extent. The sole exception is clozapine – do not switch the patient from clozapine – the patient will relapse dramatically and quickly. Changing antipsychotic medications should be undertaken in consultation with the patient’s psychiatrist.

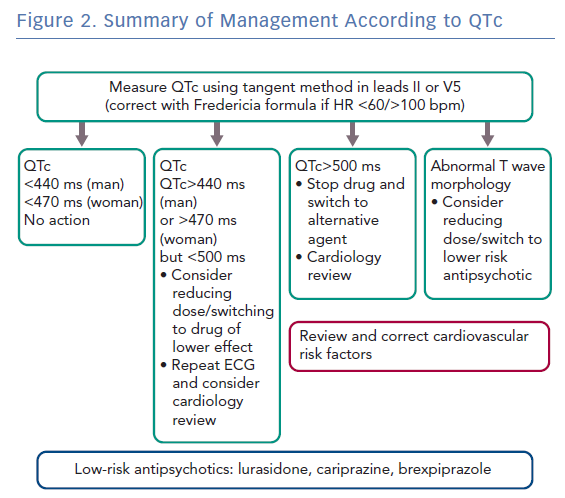

Action to be Taken According to QTc

A summary of management according to QTc is shown in Figure 2.

QTc <440 ms (Men) or <470 ms (Women)

No action required unless abnormal T-wave morphology – consider cardiac review if in doubt.

QTc >440 ms (Men) or >470 ms (Women), but <500 ms

Consider reducing dose or switching to drug of lower effect; repeat ECG and consider cardiology review.

QTc >500 ms

Stop suspected causative drug(s) and switch to drug with a lower effect: immediate cardiology review is needed. If the patient has syncope or pre-syncope, immediate ECG monitoring for ventricular arrhythmias should be performed.

Abnormal T-wave Morphology

Review treatment. Consider reducing dose or switching the patient to a lower risk antipsychotic, i.e. lurasidone, cariprazine or brexpiprazole.

Clozapine has a small effect on QTc. An implantable loop or closer 24-hour Holter recording may need to be considered if the QTc is persistently prolonged over 500 ms to check that the patient is not developing ventricular arrhythmias.

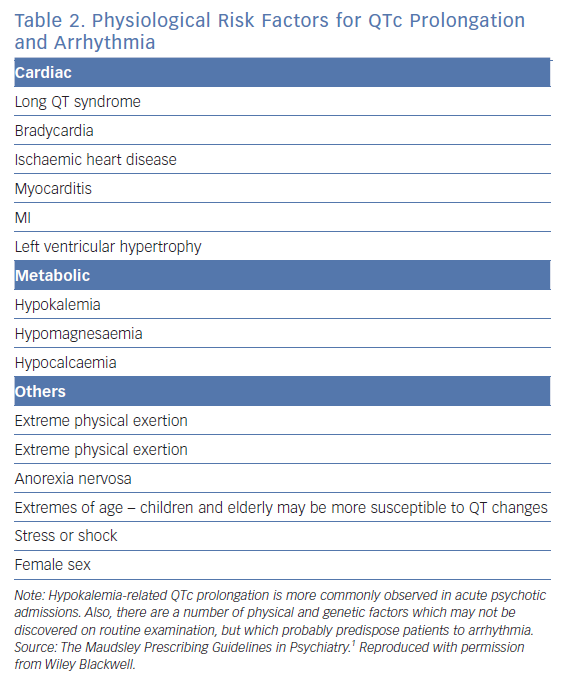

Cardiology review is necessary to specifically assess if the QTc measurement is accurate and there are no other factors leading to QT prolongation, including the cardiovascular risk factors or structural heart disease highlighted in Table 2.

Recommended Cardiology Assessment

A cardiology/electrophysiology expert review should consist of an ECG, echocardiography, 24-hour Holter and electrolyte monitoring, and liver function tests. If there are features in the history or investigations suggestive of coronary artery disease, it is prudent to undertake a CT coronary angiogram, as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance.15

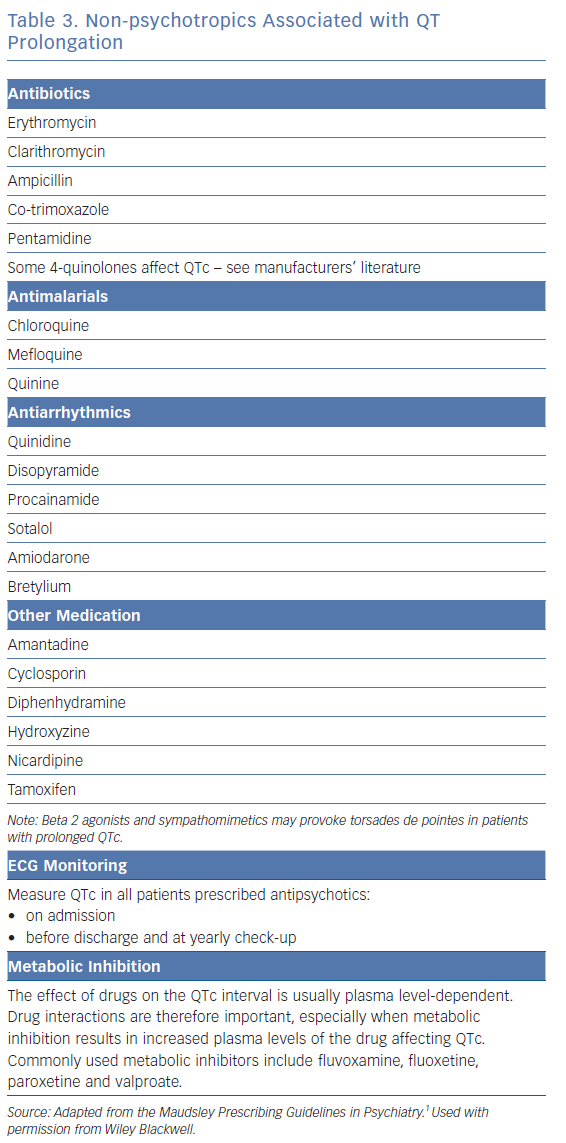

Reversible causes of QT prolongation independent of the psychotropic drug effect should be assessed. These include other QT-prolonging drugs, agents that alter the metabolism of the antipsychotics to prolong half-life and electrolyte abnormalities (Table 3). If no reversible cause is identified apart form the antipsychotic drug, an alternative agent should be employed.

Consideration should be given to inherited causes of QT prolongation; a significant proportion of drug-induced cases with a large degree of QT prolongation are associated with ion channel mutations.16 This can be evaluated by assessing persistent features of repolarisation abnormalities after stopping the drug for five half lives and examining the family history to see if there are any indications to suggest an inherited channelopathy, e.g. family history of sudden death at a young age, cot death, epilepsy, congenital deafness as well as ion channel mutation testing when clinically indicated (see the section in the Heart Rhythm Society guidelines on gene testing for inherited arrhythmias).17

Other cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, obesity and impaired glucose tolerance should be considered, because they may present a much greater risk to patient morbidity and mortality than the uncertain outcome of QT changes. These should be managed accordingly, e.g. with statin treatment as per current guidelines.

ICD Implantation

There are no systematic data on the use of prophylactic pacing or ICDs in this population and therefore it is not addressed in the current Heart Rhythm Society and European Society of Cardiology guidelines, which focus on minimising QT prolongation.

Device implantation in such patients may be difficult because their mental state may affect their ability to tolerate an ICD, which may exacerbate their psychiatric condition. The decision to implant an ICD therefore requires careful consideration. Prophylactic ICD implantation may be considered if the patient is developing non-sustained torsades de pointes or the QTcs are consistently very prolonged (e.g. >550 ms), or if a reversible cause such as stopping the antipsychotic is contraindicated due to the severity of the psychiatric condition.

Secondary prevention for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest or sustained haemodynamically compromising ventricular arrhythmias is appropriate if a reversible cause cannot be corrected and the patient is able to accept an ICD and comply with follow-up, which may be easier in the current era of home monitoring.

A dual chamber device to enable atrial pacing at 70–80 BPM and minimise QT prolongation or short-long-short pauses to trigger to torsades de pointes is advisable, although emerging data describe subcutaneous ICDs being employed in people with long QT syndrome.

In cases where symptoms of pre-syncope or syncope are suspected due to ventricular arrhythmias, an implantable loop recorder may be considered (if the patient is amenable) to correlate symptoms with arrhythmia and hence guide management.

General Principles

- Assume all antipsychotics carry an increased risk of sudden cardiac death.

- Prescribe the lowest antipsychotic dose possible and avoid polypharmacy/metabolic interactions.

- Perform ECG on admission, before discharge and at yearly check-up.

- Consider measuring QTc within a week of reaching therapeutic doses of moderate-/high-risk antipsychotics.