Although the exact circuit of atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT) still eludes us, AVNRT is the most common regular arrhythmia in humans, and therefore the most commonly encountered during ablation attempts for regular tachycardias.1–4 Catheter ablation for AVNRT is the current treatment of choice in symptomatic patients. It reduces arrhythmia-related hospitalisations and costs, and substantially improves quality of life.5–16 Catheter ablation approaches aimed at the fast pathway have been abandoned; slow pathway ablation, using a combined anatomical and mapping approach, is now the method of choice. This approach offers a success rate of 95 %, has a recurrence rate of approximately 1.3–4.0 %, and has been associated with a low risk of atrioventricular (AV) block that in most, but not all, studies is <1 %.9,10,15,17

How true are these assumptions, however, in the current era of catheter ablation? Recent reports have provided useful insights into the technique and complications associated with catheter ablation,and several myths have been refuted, outlined below.5,18–20

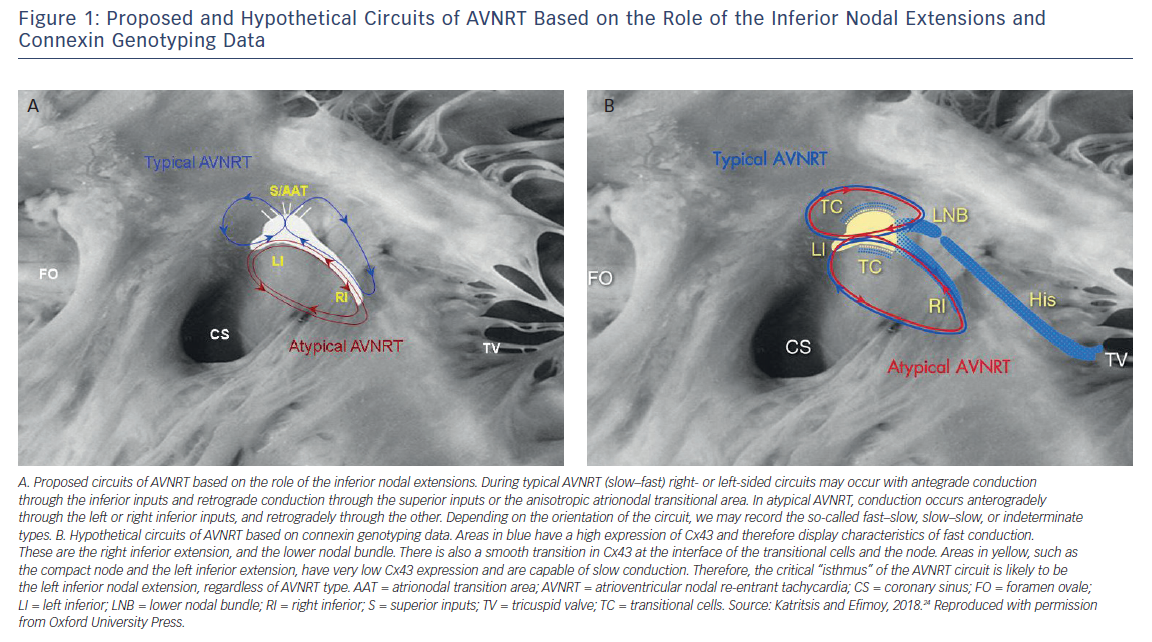

We know now that the inferior nodal extensions represent the anatomical substrate of the slow pathway in all forms of AVNRT.4,21–23 The only legitimate question that still remains unanswered is the relative importance of the right and left extensions. Connexin staining and genotyping studies have identified the left inferior extension and the AV node itself as areas of low connexin 43 (Cx43) expression, and consequently slow conduction, thus suggesting that this is the main substrate of the slow pathway (Figure 1).24

The inferior nodal extensions at the inferior (posterior) part of the triangle of Koch and below the coronary sinus ostium, as depicted in the right anterior oblique projection, are the appropriate targets for successful ablation, either from the right or left septal side.18–20,25 Slow pathway ablation or modification as described is effective in both typical and atypical AVNRT.19

It is no longer necessary to create higher lesions or perform mapping during tachycardia. These techniques are obsolete and potentially dangerous, as they can damage the AV node.26,27 There is no “upper pathway” in the AVNRT circuit, and the concept of a “lower common pathway” is disputed and of no practical significance.28

Residual dual AV nodal conduction is not predictive of recurrence, and its abolition should not be sought at the expense of prolonged ablation.20 Non-inducibility of the arrhythmia, usually after ablation-induced junctional rhythm and despite isoproterenol challenge, is the most credible endpoint for success.5,18–20

This procedure can be accomplished in both typical and atypical AVNRT with no risk of AV block. We now have substantial evidence demonstrating that we can offer a radical cure for this arrhythmia without any subsequent need for permanent pacing.5,18–20

Acute success rates as a result of rendering the tachycardia non-inducible can be achieved in all patients. Recurrence rates are 2 % in typical and 5 % in atypical AVNRT.18,19 Recurrence is usually seen within the 3 months following a successful procedure in symptomatic patients with frequent episodes of tachycardia.20,25,29,30 However, in those aged ≤18 years, recurrence may occur up to 5 years post-ablation.31 Success rates are lower (82 %) and the risk of heart block higher (14 %) in patients with complex congenital heart disease.32

Advanced age is not a contraindication for slow pathway ablation.33

The pre-existence of first-degree heart block carries a higher risk of late AV block and the avoidance of extensive slow pathway ablation is preferable in this setting.34

Cryoablation may carry a lower risk of AV block, but this mode of therapy is associated with a significantly higher recurrence rate.35–37 Its favourable safety profile and higher long-term success rate in younger people make it especially attractive in children.38

There is no procedure-related mortality in most published studies, although in the Latin American Catheter Ablation Registry there was one death (corresponding to 0.02 % mortality) following tamponade.39 I believe that there is no such risk associated with AVNRT ablation in experienced centres today.