The ideal pacing site in the ventricle(s) of patients with atrioventricular (AV) block has been debated for years. Despite considerable technological advances, the optimal ventricular pacing site to mimic normal human ventricular physiology and attain the best haemodynamic response remains elusive.1

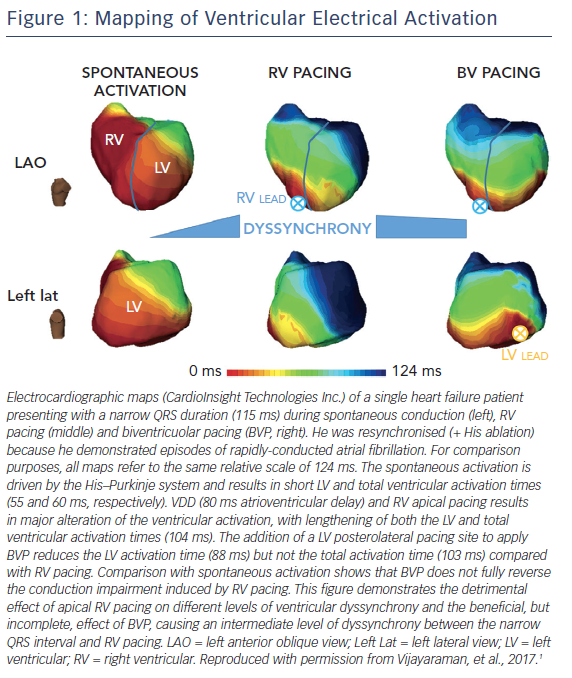

Prolonged ventricular dyssynchrony induced by long-term right ventricular (RV) apical pacing is associated with deleterious left ventricular (LV) remodelling and the deterioration of both LV diastolic and systolic function.2–4 The adverse effects of long-term RV apical pacing has led to tremendous interest in alternate pacing options. RV septal pacing sites are probably beneficial by means of intraventrcular synchrony and LV function5,6 and specific His-bundle pacing is a promising option, with acute results comparable to these of cardiac resynchronisation therapy.1,7,8 Biventricular pacing may also be superior,9 especially in patients with reduced LV ejection fraction. In the Biventricular versus Right Ventricular Pacing in Heart Failure Patients with Atrioventricular Block (BLOCK-HF) trial, biventricular was preferable to RV pacing in the presence of LV ejection fraction <50 % and AV block, but the potential for increased LV lead-related complications should be considered.10 Interestingly, in crossover comparisons His-bundle pacing has been demonstrated to effect an equivalent cardiac resynchronisation pacing response, because it generates truly physiological ventricular activation, as evidenced in part by the identical morphology between normally-conducted and -paced QRS complexes.8

Theoretically, therefore, a mid-septal position should be the optimum site, at least in patients without a previous anteroseptal myocardial infarction. Why, then, has no benefit over apical pacing been definitively shown in randomised, comparative studies?11,12 There are reasons to believe that the main problem with these trials is their relatively limited follow-up times. Deleterious apical pacing takes years to express its adverse effects on ventricular remodelling and follow-up periods of <10 years may not be indicative. In the same manner, tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathies need several years to express their adverse impact on ventricular function.13

There is a need to avoid unnecessary apical RV pacing in patients with normal intrinsic AV conduction or intermittent AV block, especially in those at risk for heart failure. If we attempt to imitate nature through artificial pacing, we should get as close as possible to the normal conduction pathway in the ventricles, by targeting the His bundle. My personal view is that we certainly need randomised trials with a reasonably prolonged follow-up to explore this important issue. This might put the death-stone on the concept of non-physiological, apical ventricular pacing.