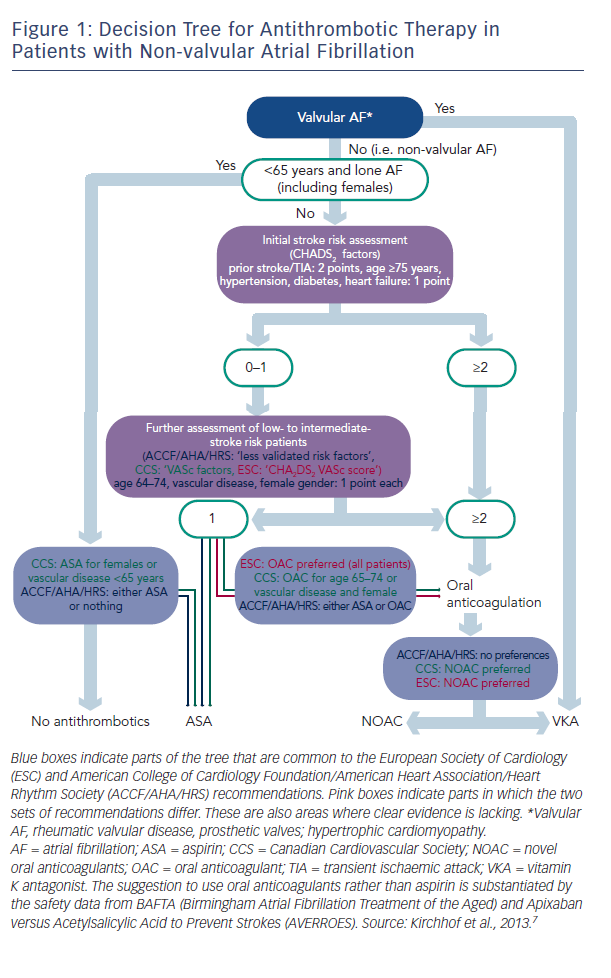

There are two types of data available to inform the use of NOACs: that from large clinical trials and that from registries, and these data are of different quality. Professor Kirchhof discussed the current treatment paradigms in valvular AF and presented a decision tree for antithrombotic therapy in patients with non-valvular AF, which combines the recommendations of current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines and those of the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) (see Figure 1).3 These recommendations show that in valvular AF, VKAs are the preferred treatment option. In non-valvular AF, the US recommendations give no preference between VKAs and NOACs, while the European and Canadian guidelines state that NOACs are the preferred option.

Although widely used, aspirin is not recommended: clinical trial data suggest that warfarin reduces the risk of major stroke, arterial embolism and other intracranial haemorrhages compared with aspirin in elderly patients.4 In addition, in a comparison of apixaban and aspirin in 5,599 patients with AF who were at increased risk of stroke and for whom VKA therapy was unsuitable, the same amount of major bleeding seen in both, but the study was terminated early because of a clear benefit in favour of apixaban.5 Lifelong oral anticoagulation is indicated for all AF patients with two or more CHA2DS2VASc (chronic heart failure, hypertension, age >65, diabetes, prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack [TIA], vascular disease, sex category) factors. Patients with only one of these risk factors may also benefit from oral anticoagulation. Almost everyone with AF is eligible for oral anticoagulation.6 In valvular AF, VKAs are the preferred treatment option. In non-valvular AF, the US guidelines give no preference between VKAs and NOACs, while the European and Canadian guidelines state that NOACs are the preferred option.7

Four landmark trials of NOACs have formed the basis for guidelines: RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy; dabigatran),8 ROCKET AF (Rivaroxaban Once Daily, Oral, Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation),9 ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation),10 and ENGAGE AF-TIMI (Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation – Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48; edoxaban).11 A recent meta-analysis of all 71,683 participants included in these trials showed that NOACs had a favourable risk–benefit profile, with significant reductions in haemorrhagic stroke and intracranial haemorrhage, but increased gastrointestinal bleeding.12 In addition, a 10 % mortality benefit was seen with NOACs.

In terms of real-world data, the GARFIELD (Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD) study, an observational study of patients newly diagnosed with non-valvular AF, found that NOACs are not being used according to stroke risk scores and guidelines, with overuse in patients at low risk and underuse in those at high risk of stroke.13 Recent 1-year data from the EORP-AF Pilot (EURObservational Research Programme-Atrial Fibrillation General Registry Pilot Phase) suggest the majority of patients (84 %) who were taking a VKA at baseline, remain on a VKA afterwards.

Likewise, patients initiated on a NOAC were likely to remain on a NOAC. Encouragingly, many patients who had received antiplatelet therapies have switched to OACs after a year.14 Another registry study, PREFER in AF (Prevention of Thromboembolic Events – European Registry in Atrial Fibrillation) found that NOACs constitute 5–10 % of use.15

The panel discussed the value of registries. It was considered that they were necessary as they generate useful data next to the phase III clinical trial data. Many patients do not participate in clinical trials because they do not meet the exclusion criteria or do not want to participate in a trial. The data generated by clinical trials can be to some extent artificial because, for example, drug intake is monitored for each patient. Furthermore, not all side-effects are picked up in phase III trials as several 100,000 people need to be exposed to the drug to reveal certain rare effects. However, registries are rarely controlled properly in terms of randomisation, therefore it can be difficult to put the results into perspective. Professor Le Heuzey considered that registries generate valuable data e.g. GARFIELD shows a lower rate of anticoagulation than in clinical trials. Registries give us an idea of the different settings in which NOACs are being used, the uptake of NOAC therapy and improved safety information, but efficacy is hard to assess. We need to know in which settings registries are run (e.g. by cardiologists or GPs) and what the inclusion criteria are for registries in order to interpret them correctly, according to Professor De Caterina. They can also help inform why data arising from clinical trials are not put into practice. For example, based on clinical trial data, the use of aspirin is discouraged in AF patients and yet registry data tell us that aspirin is still in widespread use. The PREFER registry showed that doctors treat vascular disease and AF as two independent entities so therefore when these conditions coexist, two different drugs are used. In order to maximise their usefulness, registries need more outcome data, as can be generated by pragmatic trials. NOACs perform as well in real world registries as in clinical trials but VKAs perform worse in real world data. So more trials in daily use setting are needed. In summary, the panel concluded that registry data are extremely helpful and complementary to clinical trial data and in many instances confirmatory, particularly in terms of safety.