Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia encountered in clinical practice and may be associated with symptoms, haemodynamic impairment and frightening embolic complications. In 1998 recommendations on the management of AF were reported by the Working Group of Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 1 The American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA) and the ESC published joint AF guidelines in 2001. 2 Results of major strategy trials such as the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) 3 and the RAte Control versus Electrical cardioversion (RACE), 4 and the expanding use of catheter ablation of AF prompted a revision of these guidelines in 2006. 5,6 In 2010 a new set of AF guidelines were published by the ESC 7 and in 2011 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/AHA/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) 8–10 and by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS). 11–16 The 2010 ESC Guidelines is a completely new 60 page document including 200 references. 7 The 2010 CCS Guidelines published in 2011 comprised a series of comprehensive publications on specific aspects of AF management with framed recommendations clearly separated from the rest of the text. 11–16 The 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines consisted in a main document of 98 pages with 900 references, incorporating the 2006 Guidelines and publication updates. 7–10 We reviewed these three sets of guidelines and assessed possible differences in recommendation rating, symptom evaluation, rate control versus rhythm control strategies, indications of antiarrhythmic agents to maintain sinus rhythm, anticoagulation for stroke prevention and the role of left atrial catheter ablation.

Rating Recommendations and Symptom Classification

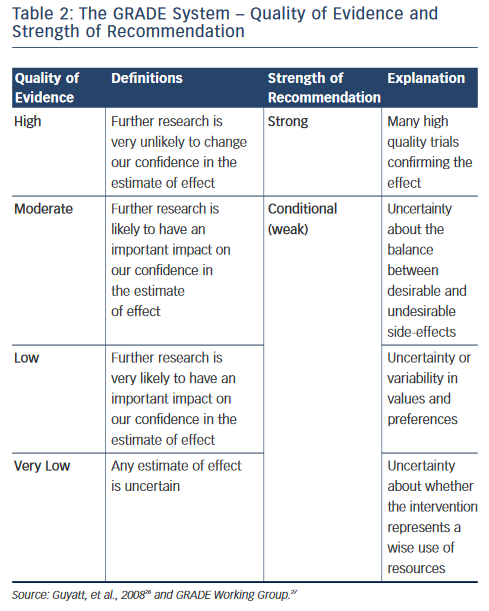

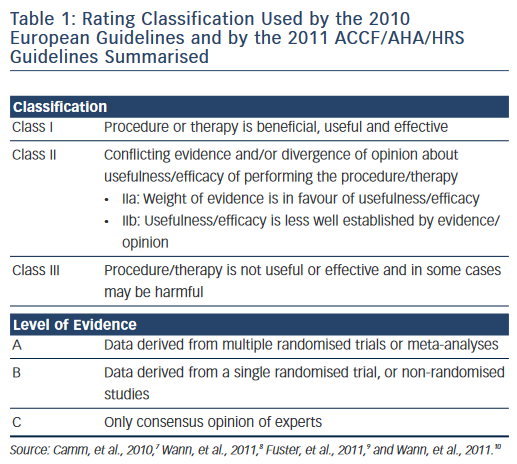

The 2010 ESC Guidelines and the ACCF/AHA/HRS used the well-known classification I, IIa, IIb and III recommendations and the level of evidence A, B and C (see Table 1 ). The CCS adopted the Grading of Recommendation Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system, which evaluates the quality of evidence (high, moderate, low or very low quality) and the strength of recommendations (strong or conditional, i.e. weak) as seen in Table 2 . 14 In evaluating symptoms, the ESC Guidelines used the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) score corresponding to no symptoms (score 1), mild (score 2), moderate (score 3) and disabling (score 4) symptoms. The 2011 CCS Guidelines used the Severity of Atrial Fibrillation (SAF) scoring system ranging from score 0 to 4 corresponding to asymptomatic, minimal, mild, moderate and severe effect on quality of life, respectively. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification is well-known with the class I–IV corresponding to no symptoms and no limitation in ordinary activity, mild, marked or severe limitation in physical activity and symptoms at rest. 17

Rate Control Versus Rhythm Control Strategy

Long-term Rate Control

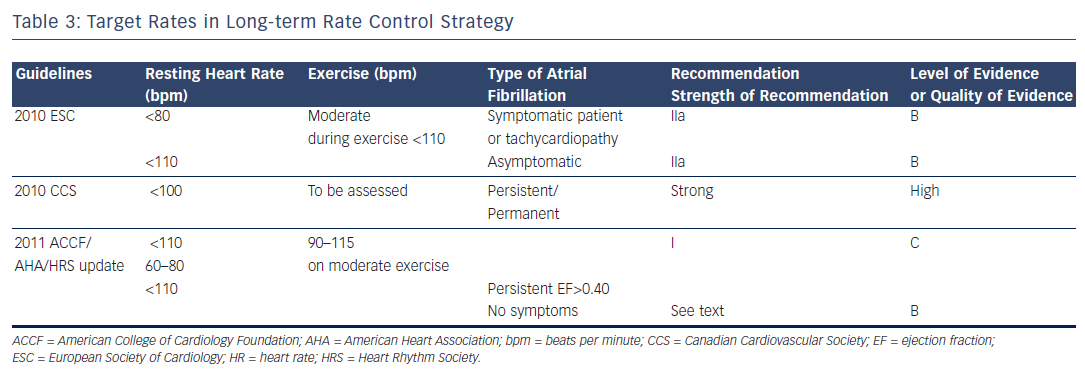

Rate control is an important endpoint in patients with persistent or permanent AF associated to rapid ventricular response in order to relieve symptoms at rest or/and during exercise. Furthermore, rapid heart rates may have an untoward effect on cardiac function and may result in tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. The 2010 ESC Guidelines consider: “reasonable to initiate treatment with a lenient rate control protocol with a target resting heart rate less than a 110 bpm” and ”to adopt a stricter rate control strategy when symptoms persist or tachycardiomyopathy occurs despite lenient rate control: resting heart rate <80 bpm and heart rate during moderate exercise <110 bpm” (recommendation IIa level of evidence B) (see Table 3 ). The 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines issued a new recommendation in persistent AF: “Treatment to achieve strict rate control of heart rate (<80 bpm at rest or <110 bpm during a 6-minute walk) is not beneficial compared to achieving a resting heart rate <110 bpm in patients with persistent AF who have stable ventricular function (left ventricular ejection fraction >0.40) and no or acceptable symptoms related to the arrhythmia...” (class III, level of evidence B). 8

Pharmacological Agents for Long-term Rate Control

Among the agents used to achieve rate control the 2010 ESC Guidelines added to beta-blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists (diltiazem and verapamil) the new agent dronedarone (400 milligrams [mg] twice daily [bid]). The ESC recommendation was before the results of the recent Permanent Atrial fibriLLAtion Outcome Study Using Dronedarone on Top of Standard Therapy (PALLAS) trial. 18 Both the ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines and the 2011 CCS Guidelines did not include dronedarone as a heart rate slowing agent.

For the 2011 CCS Guidelines, the ventricular rate at rest for persistent or permanent AF should be under 100 beats per minute (bpm), and heart rate assessed during exercise in patients with persistent or permanent AF (strong recommendation, high quality evidence). 11 Regarding the target ventricular rates, the 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines recommend target rates between 60 and 80 bpm at rest and 90 and 115 bpm on moderate exercise as seen in Table 3 . 9

The 2010 ESC Guidelines 7 recommended to select the rate-lowering agent according to the lifestyle (active or inactive) and the presence and nature of underlying heart disease. For inactive patients, the drug advised was digitalis. For those who are active the choice may be guided by the associated heart disease. Those patients with AF and no detectable heart disease or only hypertension, the choice can be made between beta-blockers, diltiazem, verapamil and digitalis. In patients with heart failure only, the use of beta-blockers or of digitalis was recommenced. In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease the use of diltiazem, verapamil or digitalis or of a beta-1 ( β 1) selective blocker was advised. The choice between lenient versus strict rate control should be based on the absence or presence of symptoms as control of symptoms by slowing the ventricular rate during AF represents an important endpoint. Regular 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), exercise testing and 24-hour monitoring may be useful to check the degree of rate control and to monitor the safety of the agent and of the dosage used.

Atrioventricular Junctional Ablation and Mode of Pacing

All three major sets of guidelines recommended to reserve atrioventricular (AV) junctional ablation to patients who failed rhythm control or/and rate control with pharmacological agents. The implantation of background ventricular pacing is mandatory with AV junctional ablation. The 2010 ESC Guidelines 7 stated that biventricular pacing was preferable to single-chamber ventricular pacing when heart failure related to systolic dysfunction or when asymptomatic systolic dysfunction was present. The 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines 9 made similar recommendations but stated clearly that in the absence of systolic dysfunction standard pacing was appropriate. The 2011 CCS Guidelines recommended biventricular pacing after AV junctional ablation in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. 11 Therefore, on AV junction ablation and pacing mode, the three sets of guidelines delivered similar recommendations.

Rhythm Control Strategy

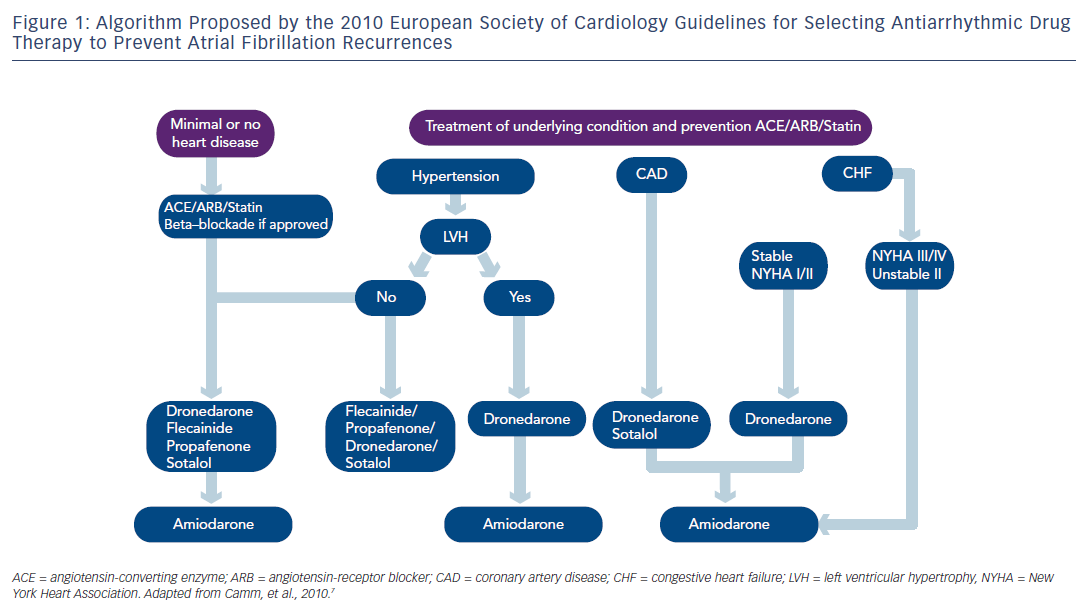

The choice of an antiarrhythmic agent, as in previous guideline editions, should be based on the presence and type of underlying heart disease. The 2010 ESC Guidelines recommend to treat the underlying heart disease when present in order to eventually prevent the development of AF or/and to use upstream therapies with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) or statins, or to use these agents for secondary prevention in specific clinical settings.

Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

The recommendation to use ACEI and ARBs for secondary prevention of AF in patients with recurrent AF undergoing electrical cardioversion on antiarrhythmic drug therapy received a class IIb with a level of evidence B by the 2010 ESC Guidelines. In the absence of significant structural heart disease, if these agents were indicated for other reasons (e.g. hypertension) the ESC Guidelines gave a class IIa with a level of evidence A for the prevention of new onset AF. The 2011 CCS Guidelines did not make any recommendation regarding ACEI/ARB. The 2011 ACCF/ AHA/HRS guidelines state: “The role of treatment with inhibitors of the RAAS in long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients at risk of developing recurrent AF requires clarification in randomized trials before this approach can be routinely recommended”.

Statins

The 2010 ESC Guidelines recommend the use of statins in “the prevention of new onset AF after coronary artery bypass grafting” (class IIa recommendation) and the “prevention of new onset AF in patients with underlying heart disease particularly heart failure, received a class IIb recommendation”. They stated that “upstream therapies and statins are not recommended for primary prevention of AF in patients without heart disease” (class III level of evidence C), 7 which contrasts with the recommendation of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/ HRS focused updates, which considered that “Available evidence supports the efficacy of statin-type cholesterol-lowering agents in maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with persistent lone AF”. 9 The 2011 CCS guidelines and the 2010 ESC Guidelines acknowledged that there was not enough evidence to recommend the use of statins for primary or secondary prevention except for post-operative AF. 7,11,19

Maintaining Sinus Rhythm Using Antiarrhythmic Agents

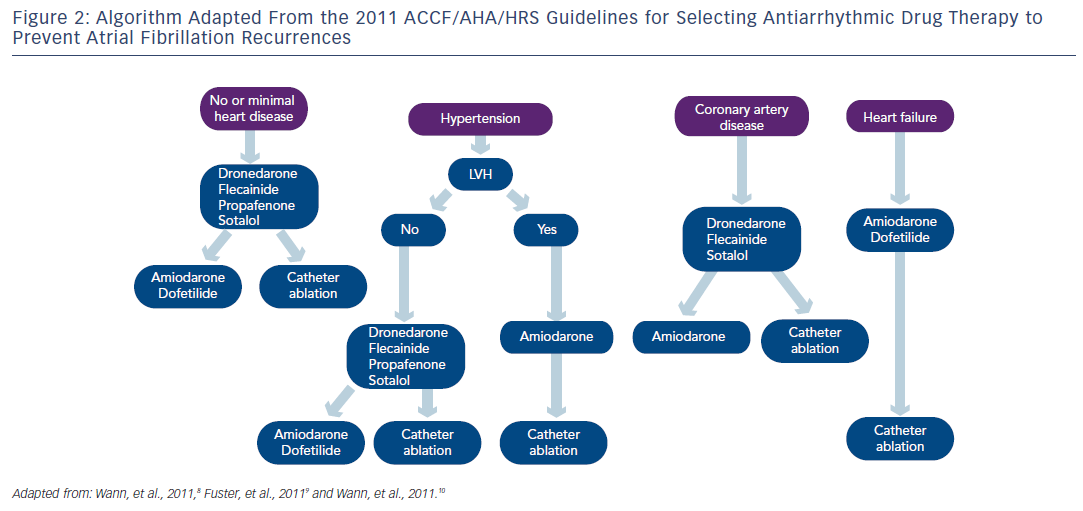

Regarding pharmacological therapy to prevent AF recurrences, the new antiarrhythmic agent dronedarone, a congener of amiodarone without iodine, represents a new option in AF management. 20–22 The 2010 ESC Guidelines recommended in patients with no or minimal heart disease, beta-blockade if appropriate and if prevention of AF recurrence was indicated dronedarone, flecainide, propafenone or sotalol and amiodarone being the last option. In patients with no heart disease, the 2010 ESC Guidelines recommended dronedarone as an alternative to conventional agents as well as in patients with hypertension and no ventricular hypertrophy (see Figure 1 ). In AF patients with hypertension and ventricular hypertrophy, dronedarone was proposed as the first option, and amiodarone as the second-line therapy. In patients with coronary artery disease, dronedarone was advised followed by sotalol and amiodarone. As seen in Figure 1, dronedarone was also proposed for patients with stable heart failure class I or II, amiodarone being the last option. The treatment algorithm proposed by the 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines 8 is shown in Figure 2 . Dronedarone was also proposed as an option in AF with no or minimal heart disease, in patients with hypertension and no significant left ventricular hypertrophy and in patients with coronary artery disease. In patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, only amiodarone was advised and in heart failure patients amiodarone or dofetilide were recommended. The 2010 CCS Guidelines recommended in patients with abnormal left ventricular function and an ejection fraction (EF)≤35 % to use only amiodarone and in those with an EF>35 % amiodarone, dronedarone or sotalol. 11 The 2011 CCS Guidelines also stated that sotalol should be used with caution in patients with EF 35–40 % and contraindicated in women over 65 years of age taking diuretics. 11

Stroke Prevention Using Oral Anticoagulation

The 2010 ESC Guidelines have adopted the CHADS 2 VASc score, which also takes into account the presence of vascular disease (V), the age (A) between 65 and 74 years and the female sex (S). 23 The 2010 ESC Guidelines stated that vitamin K antagonists (VKA) should be considered in patients with a CHADS 2 VASc score ≥1 if no contraindication was present. 7 They recommended also assessing the bleeding risk using the HAS-BLED risk score before prescribing VKA. This score includes hypertension, abnormal renal or liver function, stroke, labile international normalised ratios (INRs), elderly (>65 years) and drugs or alcohol. Each factor accounts for one point with a total of eight points, the risk of bleeding being considered high when the score is ≥3 points. 7,24

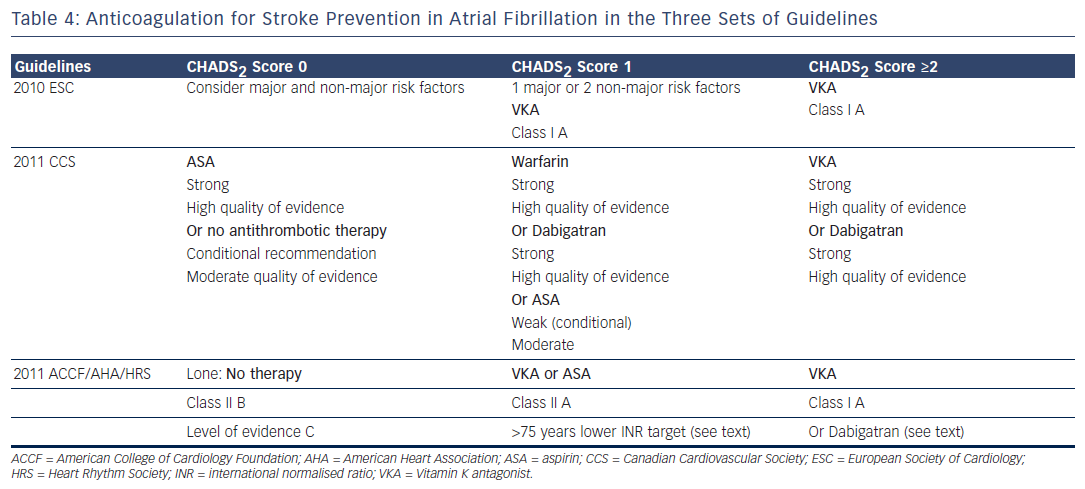

The 2011 CCS Guidelines strongly recommend aspirin (ASA) in patients with CHADS 2 score 0. The 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines recommended no anticoagulant therapy in lone AF, and VKA in patients with “more than 1 moderate risk factor”(class I level of evidence A). “In patients 75 years of age and older at increased risk of bleeding but without frank contraindications to oral anticoagulant therapy... a lower INR target of 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) may be considered...” (class IIb, level of evidence C). 9 In patients with CHADS 2 score 1, VKA is advocated by the three sets of guidelines, ASA being a possible option for the 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS and the 2011 CCS Guidelines. The latter considered the level of this recommendation as weak with a moderate strength. The 2011 CCS Guidelines proposed dabigatran as a possible alternative in patients with CHADS 2 score 1. 16 The 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS stated that dabigatran is “useful as alternative to warfarin” in patients with risk factors for stroke except for those who have a prosthetic valve or significant valvular disease, severe renal failure or advanced liver disease (class I recommendation, level of evidence C). 10 The 2011 CCS recommendations stated, “We recommend that all patients with AF or atrial flutter (paroxysmal, persistent or permanent), should be stratified using a predictive index for stroke (e.g. CHADS 2 score) and for the risk of bleeding (e.g. HAS-BLED), and that most patients should receive antithrombotic therapy. (Strong recommendation, high quality evidence)”. A similar statement is found in the 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS guidelines, “Antithrombotic therapy to prevent thromboembolism is recommended for all patients with AF, except those with lone AF or contraindications (Level of Evidence: A). The selection of the antithrombotic agent should be based upon the absolute risk of stroke and bleeding and the relative risk and benefit for a given patient (Level of Evidence A)”.

Atrial Fibrillation Ablation

Atrial fibrillation ablation is increasingly used in the management of patients with symptomatic AF. The main component of the procedure is isolation of the pulmonary veins recognised as a major focal source triggering and maintaining AF. The 2010 ESC Guidelines 7 recommended ablation of atrial flutter present before ablation or occurring during the procedure (class I, level of evidence B). For left atrial ablation, a class IIb recommendation was given to ablation of symptomatic paroxysmal AF with a level of evidence A, and a level of evidence B for persistent AF ablation. The 2011 CCS Guidelines 12 stated: “We suggest catheter ablation to maintain sinus rhythm in select patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation and mild-moderate structural heart disease who are refractory or intolerant to at least one anti-arrhythmic medication. (Conditional Recommendation, Moderate Quality Evidence)” and they add, “This recommendation recognizes that the balance of risk with ablation and benefit in symptom relief and improvement in quality of life must be individualized. It also recognizes that patients may have relative or absolute cardiac or non-cardiac contra-indications to specific medications”. The ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines considered AF catheter ablation not only as a possibility to prevent recurrences in symptomatic patients with little or no left atrium enlargement (level of evidence C) as stated in the 2006 guidelines 5 but as, “...reasonable to treat symptomatic paroxysmal AF in patients with significant left atrial dilatation or with significant LV dysfunction“. 8

Comments

Recommendation Rating

On several aspects the three sets of revised AF guidelines present obvious similarities. However, there are significant differences in the recommendation rating, assessment of the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation as pointed out by Gillis and Skanes. 25 The 2010 ESC Guidelines and the ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines used the well-known classification system summarised in Table 1, whereas the CCS Guidelines have adopted the so-called GRADE system produced by the GRADE Working Group as shown in Table 2 . 26,27 Differences in the level of evidence and of the class of recommendation between these three sets of guidelines occurred when the quality of evidence was moderate or low, as in a number of aspects of AF management randomised trials to support a recommendation are lacking. The absence of a uniform rating system and of a uniform nomenclature renders comparison of guidelines difficult. For example, it is not clear if the three sets of guidelines have been using the same definition for an ‘asymptomatic’ AF patient. Is asymptomatic, the patient who does not feel AF-generated palpitations (rapid or/and irregular heartbeats) or the patient with no symptoms at all? Aside from palpitations, well identified symptoms in AF patients include shortness of breath, chest pain, fatigue, syncope or dizzy spells. Symptoms may exist that could be related to other causes such as concomitant heart disease, associated heart failure or to another condition. 28 On the other hand, some patients complain of symptoms even when objective recordings show that AF was not present. Moreover, patients may have both symptomatic and asymptomatic episodes of AF.

Multiplication of Guidelines

The ACC/AHA/ESC Guidelines published in 2001 and revised in 2006 were a joint effort to standardise the management of AF. This effort could be supported by the fact that standards of medical practice do not significantly differ much in western countries. Furthermore, characteristics of AF patients across both sides of the Atlantic did not so far show differences. Gillis and Skanes hypothesised that multiplication of guidelines may reduce their impact on clinical practice and their implementation. 25 Surveys are showing that concordance between guidelines and their implementation in clinical practice is at best moderate. 29 Further studies are necessary to determine whether multiplication of guidelines and absence of consistency in the issued recommendations do reduce their implementation in clinical practice.

Long-term Rate Control

There is still no consensus on the optimal rate to be achieved in long- term rate control strategy. In the AFFIRM trial 3,30 the target rate was defined as <80 bpm at rest and ≤110 bpm on six-minute walk test or an average resting rate of <100 bpm on 24-hour ambulatory monitoring and no heart rate above 110 % maximum predicted age-adjusted heart rate on exercise. In the RACE trial, 4 the target resting heart rate monitored with a 12-lead ECG rate was <100 bpm.

The three sets of guidelines are referring in their recommendations to the results of the RACE II study on rate control strategy, 31 which compared the lenient resting heart rate control (heart rate [HR] <110 bpm) to the strict resting heart rate control (<80 bpm) in 614 patients with permanent AF randomised to the two strategies. The primary outcome of the study was a composite of cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalisation, stroke and systemic embolism. At three years, the endpoint was reached in 12.9 % in the lenient-control group and in 14.9 % in the strict-control group. The effect on symptoms and quality of life was not significantly different in the two groups. The authors concluded that in patients with permanent AF, lenient rate control was as effective as strict heart rate control and was easier to achieve. It should be stressed that in the RACE II trial most patients had moderate ventricular heart rates rarely exceeding 110 bpm at rest.

The 2010 ESC Guidelines proposed dronedarone as a heart rate lowering agent. This is supported by the Efficacy and safety of dRonedArone for the cOntrol of ventricular rate during atrial fibrillation (ERATO) trial results. 32 Singh et al. showed in recurrent AF a significant and consistent decrease in ventricular rate during the first AF recurrence in patients on dronedarone. 33 It was acknowledged in the guidelines that dronedarone was not approved for this indication and this indication was appropriately deleted in the 2012 focused update. 34

Dronedarone

Dronedarone was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2009 and by the European Medical Agency in 2010 in patients with recurrent AF. Comparison of dronedarone with amiodarone showed less efficacy but better tolerability. 22 Several trials have shown that dronedarone was efficient in preventing recurrences of AF. 20,33 Furthermore, the ATHENA trial showed that dronedarone had a remarkable safety profile as it reduced significantly (p<0.001) the primary endpoint (time to first hospitalisation or death) and also reduced significantly (p=0.03) cardiovascular mortality and hospitalisations due to cardiovascular events (p<0.001). 21 The ANDROMEDA trial in patients hospitalised for acute heart failure due to systolic dysfunction who received dronedarone regardless of the presence or not of AF was prematurely interrupted because of an excess mortality as compared with the placebo group. This trial raised caution for the use of dronedarone even in patients with stable heart failure or patients with asymptomatic systolic dysfunction. 35 Since the publications of the three sets of guidelines, rare liver-function test abnormalities were reported in patients taking dronedarone. In a recent report, 36 liver function test abnormalities were observed in patients on dronedarone and two patients required liver transplants without any established relation between liver injury and dronedarone. However, periodic liver-function tests are recommended for the first six months of treatment. The PALLAS trial investigated the use of dronedarone in patients with permanent AF over 65 years of age with risk factors for major cardiovascular events. 22 This trial was prematurely interrupted because of an excess risk of cardiovascular events in the dronedarone. 22 Therefore, the main indication of dronedarone at present is prevention of AF recurrences in the absence of heart failure and/or of left ventricular dysfunction (EF<35 %). The indication of dronedarone in stable heart failure class I/ II, which we thought inappropriate has been erased in the 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines, the only recommended antiarrhythmic agent in heart failure being amiodarone.

Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

The 2010 ESC Guidelines proposed, although with a question mark, the use of ACEI/ARB as upstream therapy. Supporting the use of ACEI and ARBs a number of trials, which main primary endpoint was not AF, have suggested that ACEI and ARBs may prevent AF. 37 Furthermore, there are basic mechanisms including prevention of atrial remodelling, atrial stretch and atrial fibrosis to support their use. However, there are no convincing data to recommend ACEI or ARBs to AF patients in whom they are not indicated for another reason such as hypertension, heart failure or asymptomatic systolic dysfunction as stated by Fuster et al. 9

Stroke Prevention

Differences in Stroke Risk Assessment

The recommendation for oral anticoagulation is strong in the three sets of guidelines regarding patients with CHADS 2 score ≥1. The differences in stroke risk rating constitutes a major issue as the ESC Guidelines, which have adopted the CHA 2 DS 2 Vasc, will recommend oral anticoagulation in patients for whom it will not be advised by the guidelines using the CHAD 2 score. For example, a 66 year old woman with AF and CHADS 2 score of 0 will have a CHA 2 DS 2 Vasc score of 2, which indicates oral anticoagulation in Europe and may not be anticoagulated in the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Antiplatelet Agents

Several trials have compared VKA with antiplatelet therapy. 38,39 The Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged study (BAFTA) has shown that VKA was superior to ASA 75 mg. 38 The Warfarin versus Aspirin for Stroke Prevention in Octogenarians with AF (WASPO) trial showed more bleeding with ASA (33 %) than with warfarin (6 %). 39 In the Atrial Fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events-Warfarin arm (ACTIVE W), warfarin was superior to clopidogrel plus ASA with no significant difference in bleeding. 40

The recommendation in the 2011 CCS Guidelines to give aspirin in patients with CHAD 2 score 0 is said to be strong, while the evidence of aspirin net benefit in this indication is not clearly established. Although the ESC guidelines acknowledge that aspirin is “associated with a non- significant 19 % reduction in the incidence of stroke” they still accept in CHADS 2 Vasc score 0 aspirin as a possible alternative to no therapy. 7

New Oral Anticoagulants

Dabigatran etexilate, a new thrombin inhibitor, was approved by the FDA on 20 October 2010 following the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term anticoagulant therapY (RE-LY) trial. 41 This open label trial included 18,113 patients with non-valvular AF and at least one risk factor for stroke, randomised to dabigatran etexilate (110 or 150 mg bid) or dose adjusted warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0). The primary outcome, all stroke or systemic embolism, was 1.71 % per year in the warfarin group, 1.11 % with dabigatran 150 mg reaching superiority (p<1.001 for superiority) and 1.54 % with dabigatran 110 mg being non-inferior to warfarin (p<0.001 for non-inferiority). Dabigatran is available for clinical use in the US, Canada and European countries for stroke prevention. More recently, rivaroxaban, a Xa inhibitor, was approved by the FDA in July 2011 and by the 27 countries of the European Union in December 2011 following the results of the Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET-AF) in patients with stroke risk factors. 42 This double-blind trial randomised 14,264 patients with non-valvular AF and a mean CHADS 2 score of 3.5 to rivaroxaban (20 mg daily) or to dose-adjusted warfarin. Rivaroxaban was found to be non-inferior to warfarin regarding the major endpoint of all stroke and systemic thromboembolism (Warfarin: 2.2 % per year, rivaroxaban 1.7 % per year, p<0.001 for non-inferiority). The risk of major bleeding was 3.4 % with warfarin and 3.6 % with rivaroxaban. The ARISTOTLE trial was a double-blind trial, which randomised 18,113 patients with AF to apixaban (5 mg bid), a Xa inhibitor, or to dose-adjusted warfarin. 43 The rates of the major endpoint stroke or systemic embolism, after a follow-up of 1.8 years was 1.27 % per year for apixaban and 1.60 % per year in the warfarin group (p<0.001 for non-inferiority and p=0.01 for superiority). The rate of major bleeding was 2.13 % per year in the apixaban group as compared with 3.09 % per year in the warfarin group with a reduced incidence of intracerebral bleeding and gastrointestinal bleeding. It is noteworthy that all three new anticoagulants reduced intracerebral bleeding. It is likely that these new anticoagulants will play a greater role in the management of patients with non-valvular AF for stroke prevention. It is important to emphasise that dabigatran and rivaroxaban are cleared renally and that caution should be used in patients with creatinine clearance <30 millilitres per minute (mL/min). Such patients were excluded from the RE-LY trial and from the ROCKET-AF trial.

The recent 2012 update of the CCS Guidelines stated that most patients in whom oral anticoagulation is indicated should “... receive dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban (once approved by Health Canada), in preference to warfarin”. 44 The recent edition of the American College of Chest Physicians Practice Guidelines recommended in patients with non-valvular AF at high-risk for stroke (e.g. CHADS 2 Score ≥2) dabigatran 150 mg twice daily rather than adjusted-dose vitamin K antagonist. 45 The 2012 focused update of the ESC recommend new oral anticoagulants preferably to warfarin, the latter being indicated in valvular AF and in patients with CHA 2 DS 2VASc score ≥1. 34

In predicting the risk of bleeding, a recent study compared three bleeding risk prediction scores HAS-BLED versus HEMORR(2)AGES and ATRIA. All three risk prediction scores were found to perform modestly although HAS-BLED performed better than the two other scores particularly regarding intracerebral haemorrhage. 46 In an anticoagulated AF population the HAS-BLED bleeding risk prediction score confirmed its superiority over the ATRIA score. 47 An important paper was recently devoted to bleeding risk prediction in AF patients and to its management. 48

Atrial Fibrillation Ablation

Atrial fibrillation ablation is increasingly offered to patients with symptomatic recurrent paroxysmal AF refractory to one or more antiarrhythmic drugs. The reported good results by high volume centres after one procedure of 60 % or more success rate and up to 80 % after a second procedure support such enthusiasm. The success rates in patients with persistent or long-standing AF are less impressive around 45 % and the procedure more complex. Therefore, a number of centres are advocating to intervene early in the course of AF and to offer the procedure as a first-line therapy. This attitude seems ‘reasonable’ in symptomatic young (<45 years) patients with paroxysmal lone AF who do not want to take antiarrhythmic drugs but should be limited to experienced centres. Others found this attitude debatable as the safety of the procedure, its cost-effectiveness and its long-term outcome are still raising concern. The moderate efficacy of pharmacological therapy and the side-effects, particularly the risk of proarrhythmia, is in favour of an early ablation procedure. However, it should be noted that randomised trials comparing antiarrhythmic drug therapy to AF ablation, also included patients who already failed antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Trials such as the Catheter Ablation versus Anti-arrhythmic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation Trial (CABANA) are currently conducted to evaluate the effect of catheter ablation as compared with antiarrhythmic drug therapy on mortality as the primary endpoint and also provide information on the effect on quality of life and on cost-effectiveness. 49 The recent statement of the HRS, EHRA and European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS) gave to symptomatic AF prior to initiation of antiarrhythmic drug therapy with a class I or III antiarrhythmic agent a class IIa recommendation level of evidence B for paroxysmal AF, and a class IIb level of evidence C for persistent or long-standing persistent AF. 50 Another aspect is the role of long-term oral anticoagulation post-AF ablation procedure. Some patients, although asymptomatic, may seek catheter ablation as an alternative to long-term anticoagulation with warfarin. There is not enough evidence to withhold oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention after a successful AF ablation procedure unless it is not indicated at the first place (e.g. patients with CHADS 2 score of 0). Furthermore, asymptomatic AF is not uncommon following successful AF ablation. This is in keeping with the HRS/EHRA/ECAS Expert Consensus Statement, “Discontinuation of systemic anticoagulation therapy post ablation is not recommended in patients who are at high risk of stroke as estimated by currently recommended schemes (CHADS 2 or CHA 2 DS 2VASc)”. 50