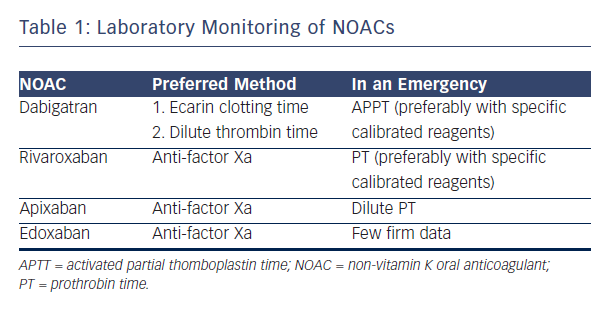

NOACs are considered controversial because of the risk of excess bleeding. It has therefore been suggested that blood levels of NOACs should be monitored. Professor Verheugt suggested that the lack of necessity for blood monitoring in NOACs is an advantage, but acknowledged that it is occasionally necessary to know blood levels and considered how NOACs could be monitored. Dabigatran, the most well-established NOAC, blocks the activity of thrombin. The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) may be used, but numerous assays for aPTT exist.21 The situation with factor Xa blockers is more complex. For rivaroxaban, prothrombin time (PT) may be used as a screening test to assess the risk of bleeding. This test is available at all times in all hospitals but the prolongation time is not impressive.22 The optimal way to measure anti-factor Xa (anti-fXa) levels is a standard laboratory anti-fXa assay: apixaban levels and anti-fXa activity show a good correlation.23 However this test is complex, expensive and not available in most institutions 24 hours a day. A systematic review showed the usefulness of standard tests: dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban show variable results on coagulation assays and linearity is not seen in the entire therapeutic range.24 In conclusion, aPTT is the only useful monitoring technique for dabigatran. For rivaroxaban, the anti-fXa assay is preferred but, in an emergency room situation, PT may be used.

The anti-fXa assay is also preferred for apixaban but in an emergency, dilute PT may be used. For edoxaban, at the moment, limited data are available to advise on laboratory monitoring in an emergency scenario (see Table 1).25

The panellists discussed the problems arising from the fact that quantitative tests involve relatively expensive tests that are not available in most institutions at all times. They also discussed whether such monitoring is, in fact, necessary. Spot measurement is needed in certain situations, e.g. bleeding or preparation for surgery when the time of last drug intake is uncertain, but these are occasional situations only. The ability to react quickly to test results is compromised by the lack of experience of laboratory staff and, given the variable response of NOACs to standard tests, each test needs to be calibrated with the specific NOAC.

In terms of routine monitoring, the panel considered that one of the great advantages on the NOACs is the lack of need to monitor, allowing increased uptake of the agents among those who need them. Despite the likelihood that some patients have higher plasma levels of NOACS than others, e.g. because of compromised renal function, these do not necessarily translate into different clinical outcomes. However, pharmaceutical companies are coming under criticism for not having developed specific monitoring tests. In certain clinical situations, e.g. if a patient presents with a large ischaemic stroke, it may be useful to have a simple assay to determine whether that patient has taken their NOAC. In rare cases of severe bleeding, it may be useful to establish whether the NOAC caused the bleeding, but again, a sophisticated, quantitative assay is not needed; we merely need to know whether or not the NOAC has been taken, and assess renal function, which is simple and informative. The consensus of the panel that was that there was no need for routine monitoring or quantitative monitoring.